The Myth of Advanced TDD

“I want to get a lot of wisdom on TDD techniques”. Many people ask me about this, especially when they sign up for my mailing list. They want the “advanced stuff”. I have good news and bad news for them: I don’t believe in “advanced TDD”. If you want advanced testing techniques, then you’re probably looking for techniques that will make your code worse, not better. (I don’t want you to do that.) If you want “advanced TDD”, then you’ve probably missed the single most important bit of “wisdom on TDD techniques”: the tests are telling you how to improve your design, so listen!

Example: Test Doubles Drive Abstraction

For example, consider the case of our good friends, test doubles—also known as “mock objects”. In particular, what about mocking method invocations—that means setting an expectation on a method invocation. Something like this:

describe "when receiving a barcode" do

example "product found" do

catalog = double("a Catalog", find_price: 795.cents)

display = double("a Display")

# This is a method expectation

# Also known as "a mock"

# We call this "mocking 'display_price()'"

# I also call this "setting an expectation on...".

display.should_receive(:display_price).with(795.cents)

Sale.new(catalog, display).on_barcode "12345"

end

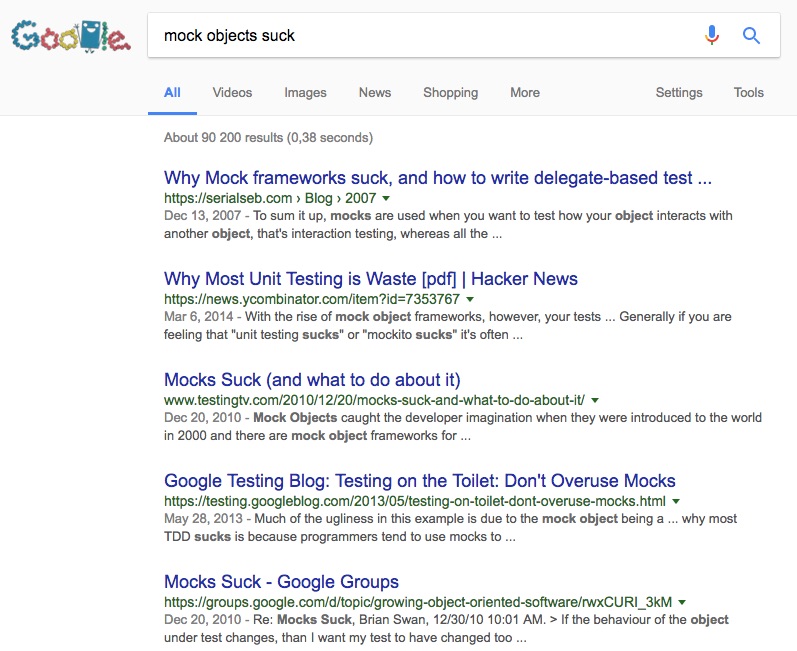

endYou can read a lot of essays about test doubles, especially under the term mock objects. Many people dislike them.

I haven’t read all these articles, but I will bet you all the money in my wallet that 90% of them fall into two categories:

- Ones that say “mock objects couple my tests too tightly to my design”.

- Ones that say “you don’t need mock objects if you replace side-effects with values (either input parameters or return values, depending on the situation)”.

Beyond Mock Objects

To the authors of the second group of articles I say, “Yes, of course.” I’ve written about this myself. Events and return values are the same thing. Many side-effects are events with a single, mandatory listener. You can replace side-effects with a value that represents the side-effect and then push the event listener up the call stack. Similarly, suppliers and values are the same thing. Many times we write code that depends on suppliers, when we have the opportunity to replace that with code that depends on the values it supplies. No stress. It doesn’t matter which design you choose if you see the equivalence between options.

Once I saw how to mechanically refactor between Supplier and Value as well as between Event and Return Value, I stopped worrying about choosing “the right design”, especially when it hadn’t yet become clear which design would fit the situation better. Now I just don’t worry about it. When it becomes clear that a Return Value fits better than an Event, I just refactor. This has the side-effect of replacing method expectations with checking value objects. Some people view this as simplifying the test; I view it as replacing one design with an equivalent one. Removing mock objects is not a goal; it’s an option.

Mock Objects Are Just Doing Their Job

To the authors of the first group of articles I say, “The test doubles are doing their job, so what’s the problem?” No, really. This “tight coupling” that the authors complain about amounts to overspecifying the behavior of the subject under test. So don’t do that. If your current design encourages you to overspecify behavior in order to write a test, then change the design. I use test doubles as a design tool specifically because they put constant positive pressure on my design and they alert me to design risks as they happen!

When you do sit-ups, that usually causes pain. Notice the way that I worded that sentence: the act of doing sit-ups causes pain. Not the sit-ups themselves, but the combination of a few things: your technique, the amount of fat around your midsection, the surface on which you sit, and the act of performing the sit-up. Imagine instead that you tried to do some sit-ups, felt pain, and then concluded “sit-ups suck, because they cause pain”. Nonsense! Sometimes your technique needs work, but often sit-ups suck because you’re fat1. The sit-ups are sending you a signal that you need to burn more fat. Sorry. Assuming that you care about how fat you are, the sit-ups are doing their job: signaling you to improve your body composition. Sadly, sit-ups provide pretty harsh feedback, so I don’t recommend them as your primary way of getting feedback about your body composition. Not everyone needs to do sit-ups pain-free. You might find another way to get that feedback.

When people say that mocking functions couples their tests too tightly to their production code, and then conclude that “mock objects suck”, they are blaming the sit-ups instead of their fat. Don’t do this. The function expectations are trying to tell you something about your design, so listen!

The example above doesn’t make this very clear. I like that test: it has a single action and a single assertion (the function expectation is an assertion). I can clearly discern the apparent objective of that test: if Sale finds a price for the barcode, then it should try to display that price. Displaying the price is the objective of the test. Clean, clear, obvious.

A More Complicated Example

Now imagine that we’ve built the features “sell multiple items/introduce shopcart”, “update inventory”, and “compute sales taxes”. Now the test looks more like this:

describe "when receiving a barcode" do

example "product found" do

product_found = Product.new(price: 795.cents, taxes: [:HST_PE])

catalog = double("a Catalog", :find_product => product_found)

display = double("a Display")

shopcart = double("a Shopcart")

inventory_gateway = double("an Inventory Gateway")

display.should_receive(:display_price).with(product_found.price)

shopcart.should_receive(:add_product).with(product_found)

inventory_gateway.should_receive(:reserve_product).with(quantity: 1, product: product_found)

Sale.new(catalog, shopcart, inventory_gateway, display).on_barcode "12345"

end

endI like this test less: although it still has only one action, it now has three assertions. Moreover, if I want to check only the inventory gateway behavior, I have to do something with the shopcart and display behaviors—either check them (who cares?) or shut them up (why force me to do this?). In similar situations, I see programmers blindly copy and paste these test doubles all over the place. They don’t think they have a choice. They start writing articles that praise mock object libraries that act like Mockito (by making “lenient” the default choice). They say things like “I like spies more than mocks” (even though they are fundamentally the same things). Worse, they start writing articles about how mock objects “suck”. Sigh.

What If We Listened To the Crying?

The design is crying, and the tests are the cries. Instead of ignoring those cries, let’s listen to them. What do they say? First, irrelevant details in a test indicate involving modules that the test would rather ignore. This means that we have an integrated test, even when it doesn’t look like we do. Injecting dependencies and using test doubles masks the problem, but doesn’t solve it.

Duplicate assertions in a test indicate a missing abstraction. Duplicate assertions? But the method expectations are all different. But are they? They have one thing in common: product_found.

A function expectation in a test indicates the presence of side effect that we can often model as an event. Morever, if we set an expectation on an action/verbal name (display price, add product, reserve product), then we can replace those expectations with an event and it means the same thing. I can think of the event as an interface and the handler as an implementation of that interface!

We can look at the patterns in the names to extract the event. Clearly, we should use the Product as the event data, but what should we name the event? When should we display the price, add the product, or reserve the product in inventory? Why… when we have found a product.

How about on_product_found(product) as the event? I like it!

I can convert all three function expectations into handlers for the product_found event. The test doubles have led me towards finding the missing abstraction.

Following the Test Doubles’ Advice

Now the test becomes simpler, because I replace three similar interfaces with a single, equivalent one.

describe "when receiving a barcode" do

example "product found" do

product_found = Product.new(price: 795.cents, taxes: [:HST_PE])

catalog = double("a Catalog", :find_product => product_found)

event_listener = double("an Event Listener")

event_listener.should_receive(:on_product_found).with(product_found)

Sale.new(catalog, event_listener).on_barcode "12345"

end

end

In order to make this work as before, I introduce a BroadcastEventListener, which broadcasts events to a collection of listeners; next I introduce event listeners for each of the three actions.

# In the entry point of the system...

sale = Sale.new(

BroadcastEventListener.with_listeners(

Display.new(),

Shopcart.new(),

InventoryGateway.connect(inventory_database)))

# ...install sale into the routing table to receive "scanned barcode" requestsI can easily implement the common interface on these classes.

class Display

def on_product_found(product)

display_price(product.price)

end

end

class Shopcart

def on_product_found(product)

add(product)

end

end

class InventoryGateway

# ...

def on_product_found(product)

reserve_product(quantity: 1, sku: product.sku)

end

endIf it worked better, then I could instead separate the event handlers from the model classes. I could even just register lambdas in the entry point.

# In the entry point of the system...

display = Display.new

shopcart = Shopcart.new # why is this a singleton? Hm. Multiple shoppers?

inventory_gateway = InventoryGateway.connect(inventory_database)

sale = Sale.new(

BroadcastEventListener.with_listeners(

-> product { display.display_price(product.price) }

-> product { shopcart.add(product) }

-> product { inventory_gateway.reserve(quantity: 1, sku: product.sku) }))

# ...install sale into the routing table to receive "scanned barcode" requests

Let’s ignore the comment about implementing Shopcart as a singleton for now. I’ve put that in my inbox, so I’ll get to it later.

I consider these event listeners too simple to break, but if you don’t, then you can easily introduce named classes for them and then check them separately. For example:

class ReserveItemForPurchaseAction < ProductFoundListener

attr_reader :inventory_gateway

def initialize(inventory_gateway)

@inventory_gateway = inventory_gateway

end

def on_product_found(product)

inventory_gateway.reserve(quantity: 1, sku: product.sku)

end

end

describe "Reserve an item for purchase" do

example "when a product is found" do

inventory_gateway = double("an Inventory Gateway")

inventory_gateway.should_receive(:reserve).with(quantity: 1, sku: sku)

ReserveItemForPurchaseAction.new(inventory_gateway).on_product_found(Product.with(sku: sku))

end

end

I can’t think of any other tests for this, can you? Here I’ve simulated the case where the InventoryGateway is some legacy service that requires clients to specify the number of items they’re reserving, even when we want to use the sensible default value of 1. If you want to check for a faulty event object, feel free, but I trust me. You don’t have to trust me nor you. I would design the other event listeners similarly.

I can implement the BroadcastEventListener to forward events without worrying about the event values themselves. This becomes generic behavior that we check once and then simply trust. To check the broadcaster, simply attach a few mock event listeners and check that all the listeners receive the same event that the broadcaster receives. If we decide to add some behavior to validate and canonicalize events, then we can add it somewhere near here.

Surveying the Results

In listening to the annoying function expectations in our tests, we did the following:

- Introduced a high-level event, “on product found”, which makes the controller-level code so simple, it becomes almost self-evidently correct: if we find the product in the catalog, the signal the event “product found” with that product.

- Extracted a highly-reusable event broadcaster. When do we start the open-source project for code like it?

- Separated completely independent actions that previously just happened to reside in the same place. Adding an item to a shopper’s shopcart, displaying the price of that item, and reserving it for purchase in the inventory system don’t need to depend on each other to behave correctly, so why should we execute the others when we care about just one of them? We can decide later how to decorate these actions with error handling: should we warn about all the failures? should we fail if there are any failures? We can add this in the controller or we can introduce another specialized event listener.

- Highlighted the business rules in the controller: when a product is found, we notify the shopcart, the display, and the inventory gateway. If you don’t like this design, then defactor it to make the controller a closed facade. I wouldn’t feel tempted to test it with programmer tests, although I would probably check the end-to-end flow with Customer Tests—just not exhaustively. I would write only as many tests as the Customer needs to feel confident that we understood each other.

I consider this a significant win. When we add another feature that requires listening to the “product found” event, we will find that really easily. Almost disturbingly easy.

“Advanced TDD?”

So, would you consider this advanced TDD? I don’t. I consider this elementary TDD: feedback from the tests drives the design. (Does anyone else remember when we went through the phase of calling it “test-driven design”?) The technique of TDD hasn’t changed; I’ve simply taken seriously the notion that if I notice problems in the tests, then they probably point to problems in the production code. If you think of this as “advanced TDD”, then I suppose I would say that advanced TDD is little more than practising TDD more diligently.

You can do it, so why don’t you try?

Epilogue: Eventsourcing

Yes, yes. Eventsourcing blah blah blah. I get it. If I have techniques that nudge me towards extracting the events, then I feel good: even when I don’t use eventsourcing, I find the events anyway. Win-win.

Reactions

A great article about how letting tests drive your design makes your code needlessly complicated and your tests less powerful. Don’t think the author meant it that way, though. Also, he doesn’t understand sit-ups. https://t.co/X4gSxyTudm

— Tom Anderseine (@tomwhoscontrary) November 17, 2017

I don’t include this to draw attention to any one person. On the contrary, I’ve heard this particular argument before. Tom elaborates:

Broadly, though, the area of code and number of places in the codebase you have to look to understand something (“what happens when we scan a barcode?”) has increased, and that makes it more complex.

I have written about this elsewhere: “Modularity. Details. Pick One.”. In short, lack of modularity and obsession with details creates a positive feedback loop; introducing abstractions breaks the pattern. Well-named, well-designed abstractions make me more likely to trust modules (classes) and therefore not need to look at their details.

In this way, I make systems out of simpler compositions of easier-to-combine pieces. I separate technology-oriented code from the business rules, so that the latter stand out more. I think I’ve achieved that here with the three listeners to the product_found event, although we can argue about how exactly to write those three lines. In particular, I believe I’ve replaced one place to look for this behavior with… one place to look for this behavior! I don’t need to know how those three listeners achieve their goals. That reflects the trust earned by modularity and helpful names.

People in the industry have been telling us this since the 1960s, even when they wrote about structured programming. Modularity has never gone out of style. The functional programming crowd is now beating this drum quite hard; we merely have more freedom in object-oriented designs and so need to constrain ourselves more to achieve modularity. The technique that I’ve outlined here shows one example of how I use tests to arrive at these abstractions so that I don’t have to “see” them up front.

References

J. B. Rainsberger, “Beyond Mock Objects”. Don’t depend on a supplier when you have the opportunity to depend on the value that it supplies.

J. B. Rainsberger, “JMock v. Mockito, But Not To the Death”. JMock helps me avoid accidental complication in my design by nagging me; Mockito avoids nagging me while I remove accidental complication from legacy code.

J. B. Rainsberger, “Modularity. Details. Pick One.”.

J. B. Rainsberger, “Abstraction: The Goal of Modular Design”.

-

No, I’m not body shaming anyone. I used to be over 70 kg overweight. “Being fat” is just a fact of life for some people. I don’t use it as a criticism. I was fat. I’m now much, much less fat. If you want proof, find any video or photo of me from 2011 or earlier.↩︎