A Matter of Interpretation: Mock Objects

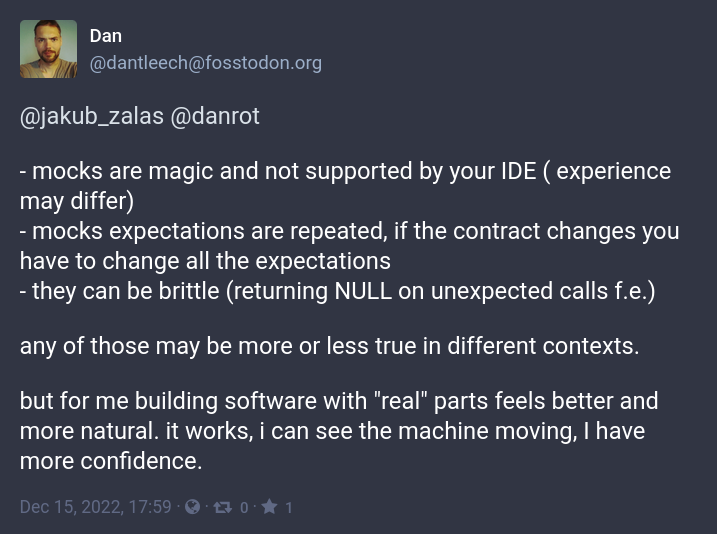

In the middle of a discussion about test doubles/mock objects and their role in design, someone posted this:

I’d like to focus on these parts1:

- “mocks expectations are repeated, if the contract changes you have to change all the expectations”

- “for me building software with ‘real’ parts feels better and more natural. it works, i can see the machine moving, I have more confidence.”

I interpret these two statements in a way that changes how I relate to them. If you’ve struggled with using test doubles as a design tool, then maybe you would find these additional interpretations helpful. Let’s see!

Remove Duplication!

When I see expectations repeated in tests, I look for ways to remove that duplication. Removing duplication tends to improve my designs, even if it sometimes takes some persistence or patience to see those changes as improvements. I have grown to trust that my future self will regret ignoring the design risks that my present self often feels are “not worth the effort” to address right now.

How to remove that duplication? Two options immediately come to mind, depending on the nature of the duplication.

- Introduce a thin layer around the test doubles to hide the implementation details, revealing intent and respecting the guidelines of the Universal Architecture.

- Introduce a higher-level abstraction that replaces a group of related expectations with a single expectation. Raising the level of abstraction often simplifies the resulting interactions.

For my purposes in writing this article, I don’t need to know how to remove duplication here. Instead, I want to highlight my design process: I welcome the duplication, because I interpret it as a beneficial refactoring opportunity. I routinely work with programmers who don’t interpret the situation this way, but instead copy and paste these expectations from test to test, typically either because they feel stuck or because they feel rushed. Maybe they don’t know how to improve the design, maybe they don’t have the authority, or maybe they can’t justify taking the time. Whatever the reasons, they wouldn’t interpret the duplication as a signal to refactor, but rather as an unavoidable fact of life. A trap.

I don’t want to criticize anyone’s interpretation. I merely want to mention that I have trained myself to use this duplication as a signal to refactor and I make a conscious decision whether to refactor or not. And I usually refactor, but even when I don’t, I add a REFACTOR comment to remind my future self what to do when I finally decide to stop resisting. And sometimes future me has an even better idea when it gets there.

As a result, I see this pattern of duplicating expectations as a strength, not a weakness. I interpret this as test doubles doing their job, not as a drawback to using them. Indeed, test doubles make this design risk visible and difficult to ignore in a way that other forms of Lightweight Implementation sometimes hide. I want that—or at least I’ve grown to like it. Maybe you can, too. You might even like it.

It “Feels More Natural”; It’s “More Real”

Many programmers tell me that it feels more compelling to integrate a module with the production implementations of its neighboring collaborators. They even call those things “the real implementation”, which reinforces the notion that modularity and abstractions are somehow “fake”. I understand where this feeling comes from, even though I don’t share it any more.

In my work I often encounter programmers with this belief. I sometimes challenge this belief by asking them a question:

I assume you write code that uses lists. I assume your language has at least two implementations of lists: one backed by an array and another implemented as a linked list. How confident would you feel about the correctness of your code if I randomly replaced a bunch of array lists with linked lists? (Ignore the execution speed issue. And assume that I changed nothing else.)

Almost always they tell me that they don’t mind. They feel equally confident using a linked list implementation compared to an array list implementation.2

The next question makes all the difference.

Why? Why not insist on integrating everywhere specifically with a consciously-selected implementation of list?

Their answers tend to boil down to this: “I trust that the implementations of List that I use respect the Contract of List.” They rarely use those exact words, but they almost always agree with that statement when I say it to them.

I have experienced a wide variety of the reasons why they trust those implementations of the their list data type3, but there is one consequence of that trust that comes up every time: they think of lists directly as lists (the abstraction) without needing to think about the choice of implementation module (class, object, whatever). They don’t always think like this, but it becomes their default way of thinking. They tend to consider the implementation details only when they worry about performance characteristics or when they work in a programming language where they can’t delegate memory management to the runtime environment. Whenever they have the opportunity, they ignore the very existence of different implementations of the abstract type “list”. And they find that freeing. So do I!

Good! Two more questions:

- Wouldn’t you like to feel that freedom in more parts of your design?

- What stops you from feeling that freedom?

That leads us into a discussion of Collaboration and Contract Tests as a way to gain confidence in ignoring the implementation details behind purely abstract data types (also known as interfaces, protocols, or roles). That tends to lead to a discussion about the value of increasing trust in the Contract of their own abstractions and subsequently needing less often to integrate directly with “the real thing”.

In other words, if you need to integrate with “the real thing” to feel confident in your code, then you don’t trust the Contract of your neighboring collaborators. You can gain that confidence with integrated tests or with contract tests; you can choose. I feel comfortable doing both, although if you don’t trust those Contracts somehow, you’ll find yourself stuck with integrated tests whose cost to maintain only increases (at an accelerating pace!) over time. Give yourself options!

-

I don’t experience the other problems that this person reports, but I also don’t feel any need to quibble. They experience what they experience.↩︎

-

Many programmers are even surprised that such a thing is possible! They use lists without even knowing that they’re using a purely abstract type and not a specific implementation. That makes my point even more strongly.↩︎

-

“The contract is small.” or “I only use a small part of the interface.” or “The implementations have been around for 20 years.” or “The core programmers of the language know what they’re doing.” or “The client base of this interface is huge, so the implementations must work.” or “This abstraction is so central to writing code that if it didn’t work, the language would have disappeared by now.”↩︎