Putting An Age-Old Battle To Rest

So maybe not an epic, age-old battle, but a battle nonetheless. The battle over the correct ordering of the Four Elements of Simple Design. A battle that I’ve always known I’d won, but until recently, could never justify to others. I can finally declare victory and bestow upon you the One True Sequence.

Calm down; I’m joking.

Seriously: it has always bothered me (a little) that I say it this way and Corey Haines says it that way, and somehow we both have it “right”. I never quite understood how that could happen… until now.

I learned these “rules” of simple design—guidelines, really—from the work of Kent Beck. He suggested the following guidelines as a definition of “simple”.1 He calls code “simple” if it:

- passes its tests

- minimises duplication

- reveals its intent

- has fewer classes/modules/packages…

He mentioned that passing tests matters more than low duplication, that low duplication matters more than revealing intent, and that revealing intent matters more than having fewer classes, modules, and packages.

I grew up (as a programmer) with these rules, and they have guided me well. My friend and colleague, Corey Haines, however, obstinately insists on reversing the order of “remove duplication” and “reveal intent”. He presents the four elements of simple design this way:

- pass the tests

- reveal intent

- don’t repeat yourself

- fewer classes

Corey hasn’t cornered the market on interpreting Beck’s rules in this order. If you search the web, you’ll find a surprising number of articles about the four elements of simple design advocating either sequence of rules. Some articles probably even argue quite loudly in support of ordering the rules one way or the other.

I have finally figured out why this happens. At least, I think I have. And I have good news: we all have it wrong.

I don’t think it matters whether you focus first on removing duplication or on revealing intent/increasing clarity, because these two guidelines very quickly form a rapid, tight feedback cycle. By the time the guidelines guide you to any useful results, you’ll have probably used them both. Therefore, order the rules however you like, because you’ll get to the same place either way.

Nice, isn’t it?

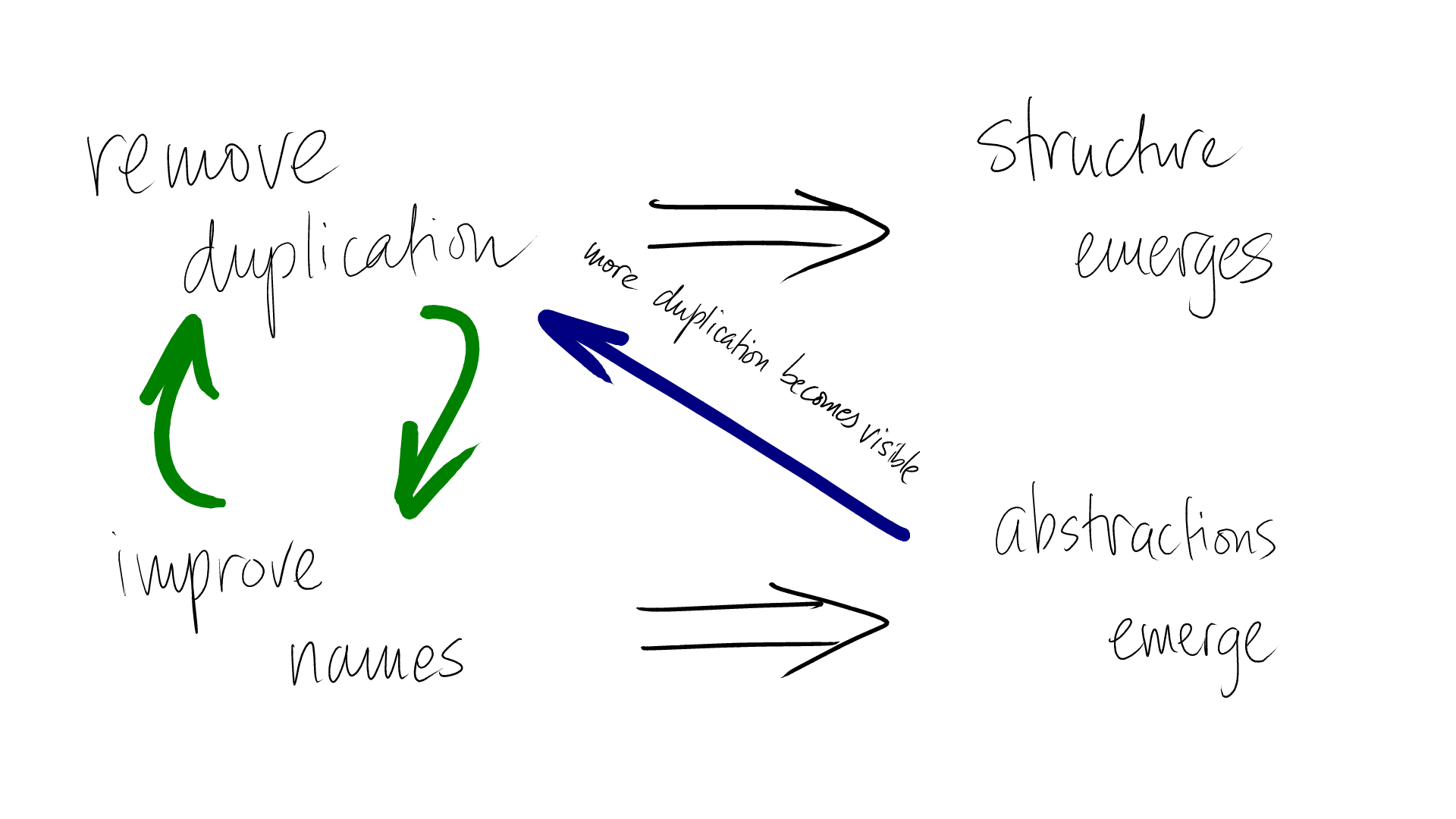

What I Think Happens

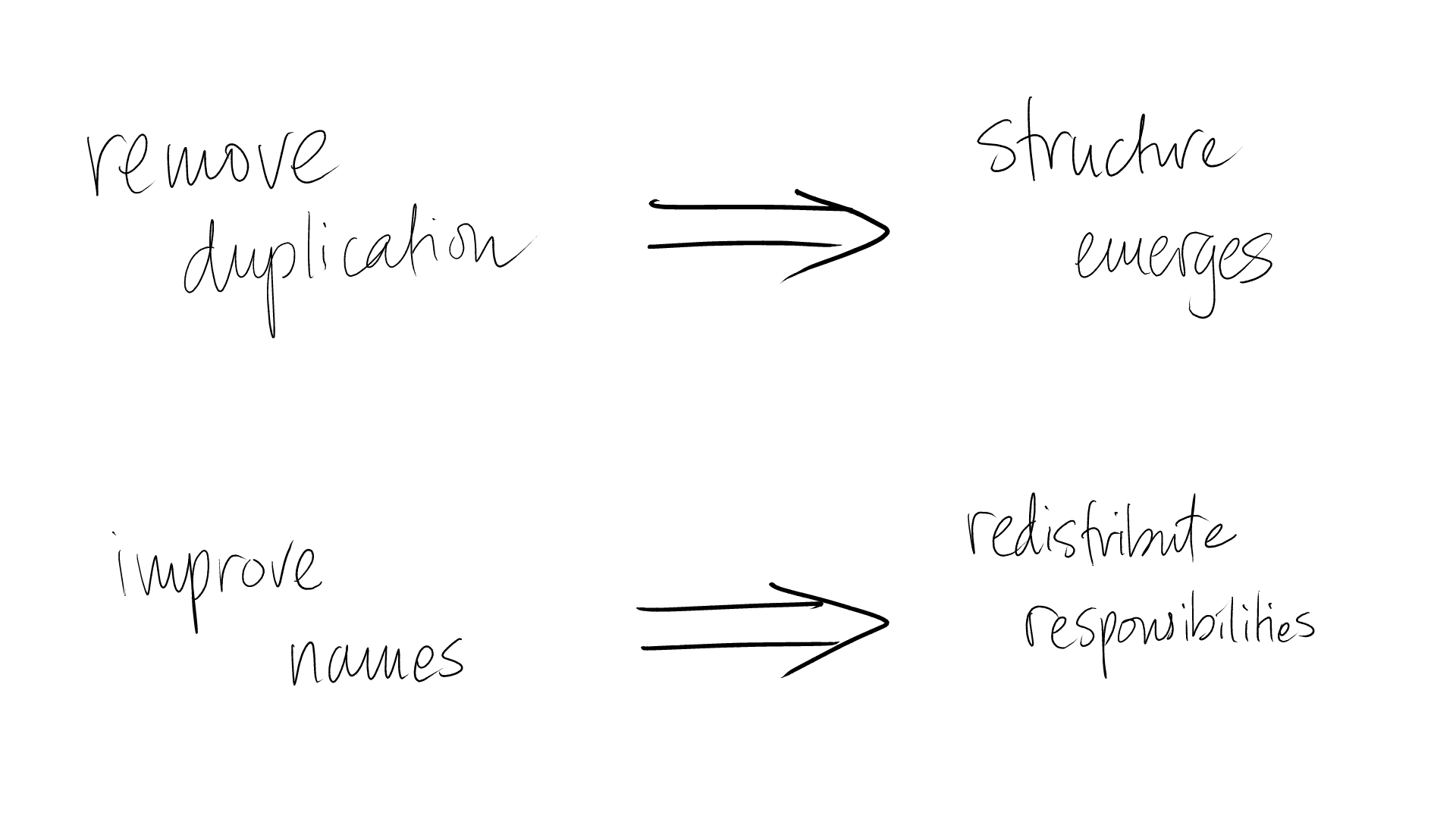

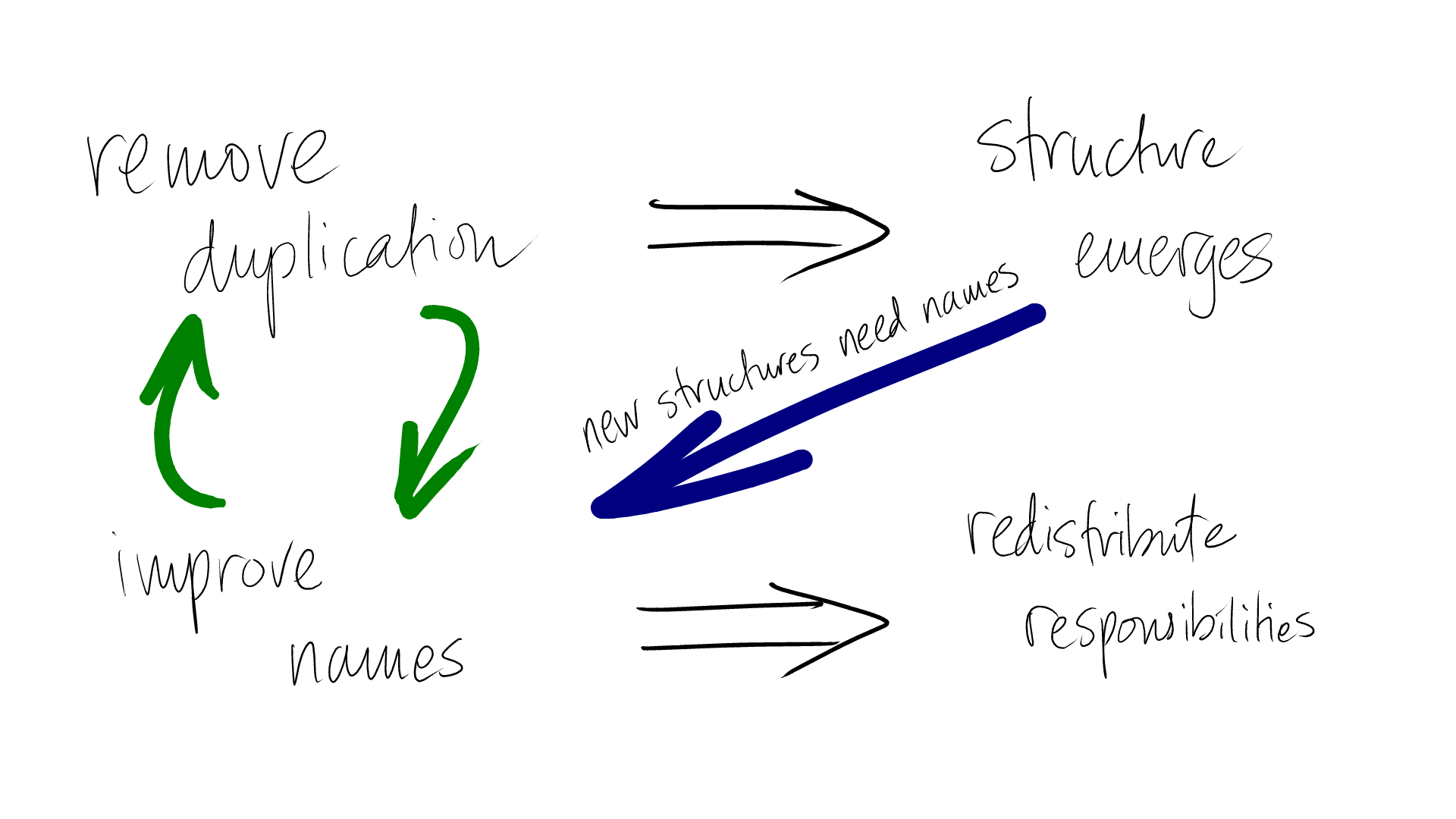

I have noticed over the years that when I try to focus on removing duplication, new, useful structures emerge. I like to say that if the solution wants to be structured a certain way, then removing duplication helps that structure to emerge.2 I have also noticed that when I try to focus on improving names, Feature Envy and its friends become more apparent, and code makes it clearer that it wants to move somewhere else. Similar concepts scattered throughout the system start calling out to each other, hoping for the programmer to unite them in a single module. Crowded, unrelated concepts struggle to get away from one another. Responsibilities gradually move to a more sensible part of the code base. Both of these contribute to higher cohesion.

But wait; there’s more.

Whenever we create new structures in code—extracting methods, functions, classes, modules—we have to give these new structures names. We never really like these names, so we always seek to improve them.

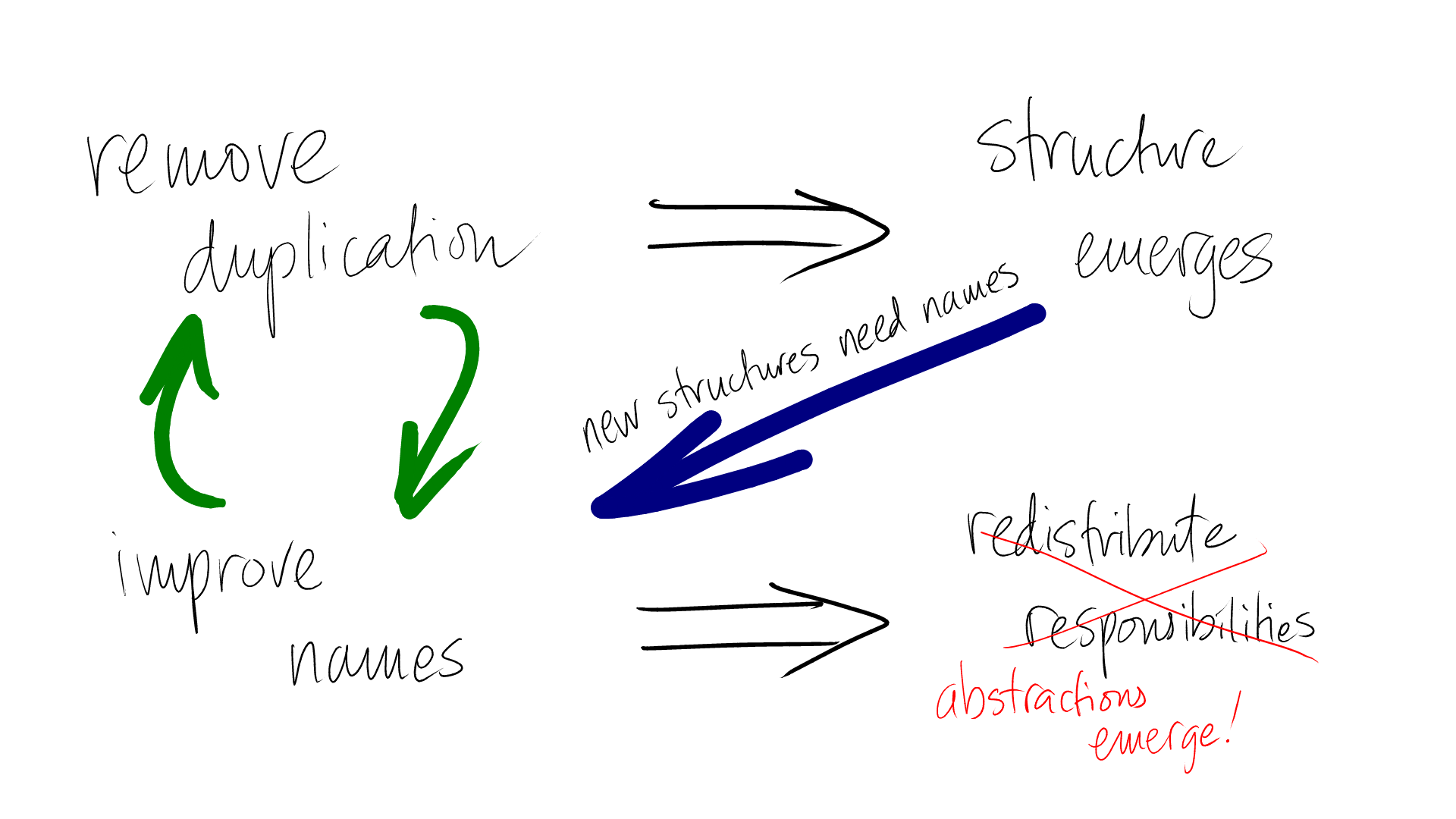

As the names improve, cohesion improves, so that similar things move closer together and different things move farther apart. Removing duplication creates buckets and improving names redistributes the things among the buckets. Over time, the rest of the system—the clients of these buckets—treat the buckets more like single things rather than collections of things. We call this abstraction.

But, of course, at this higher level of abstraction, we get away from those details and start seeing new patterns in bigger things. That means more duplication.

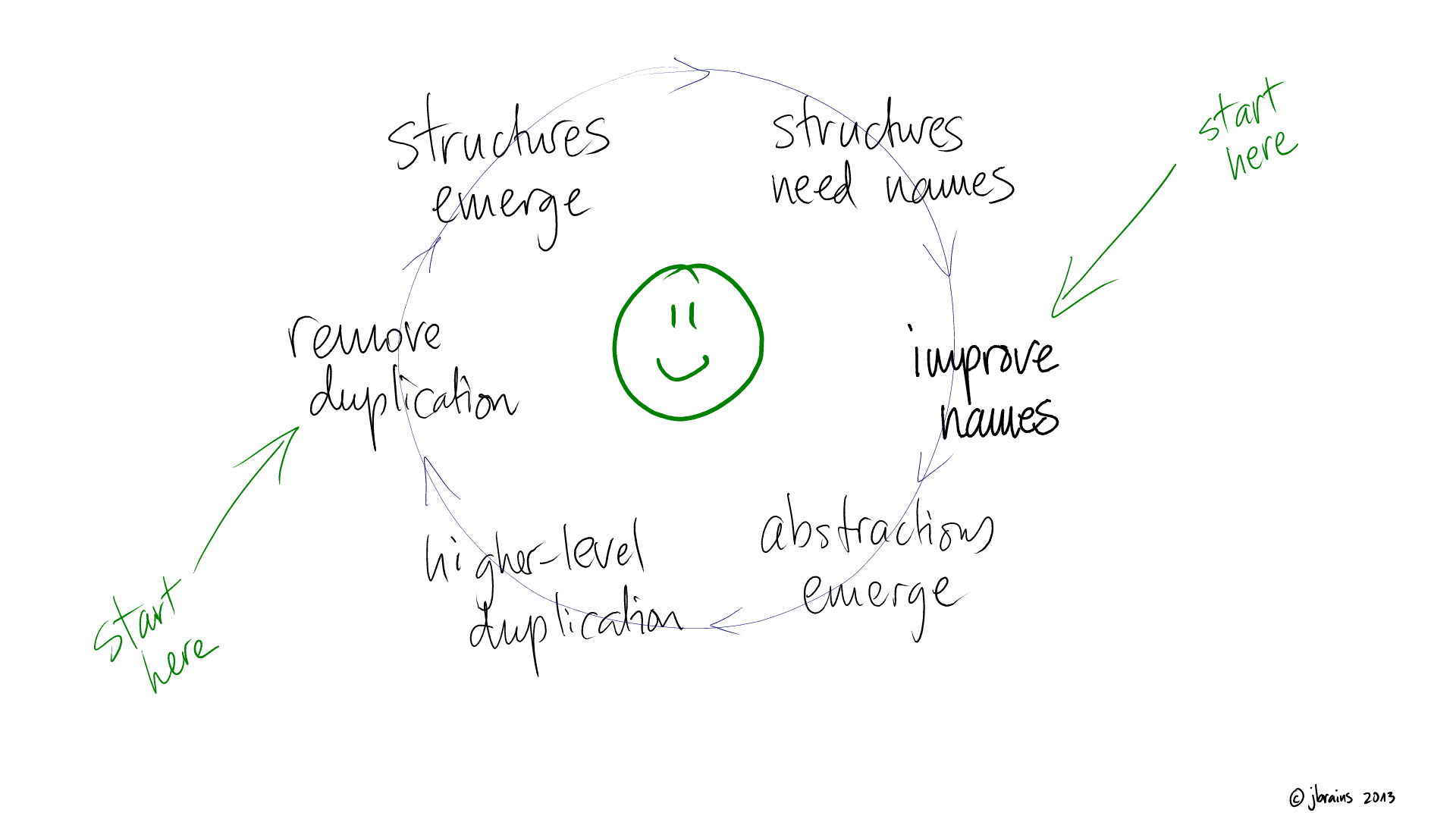

We see duplication, then we remove it. We need to give these new structures names. We want to improve those names. In the process, more details slip away and more abstractions emerge. We raise the level of abstraction again.

And again.

And again.

This describes a way to organize code into helpful layers with beneficial abstractions, rather than leaky indirection. When we remove duplication, we create buckets; when we improve names, we create more cohesive, more easily-abstracted buckets. We need them both and we just keep going. I don’t see a big difference when I start by removing duplication, compared to when I start by improving names.

The Four Elements of Simple Design Revisited

I have been teaching for years about how to reduce the four elements of simple design to two: after several months, I don’t think about writing tests any more—I simply call that “programming”—and I’ve never seen a well-factored code base that had an order of magniture too many elements. With these two points out of the way, I guide my design with two basic rules: remove duplication and improve names. I’ve started thinking about these guidelines a little differently.

Now, I think of them as a single guideline: remove duplication and improve names in small cycles. When I do this, I produce a higher proportion of well-factored code compared to all the code I write. I use tests to clarify the goal of my code and to put strict limits on how much code I write.

Tests help me limit the amount of code that I write. Removing duplication and improving names helps me reduce the liability (cost) of the code that I write. Together, they help me reduce both the total cost and the volatility of the cost of the features I deliver.

I think this suffices as a working definition of “writing the code right”, which complements the need to “write the right code”. I have a whole bag of tricks to help do this well, which I call Product Sashimi Value-Driven Product Development.

Reactions

Of course, just as I use Corey as the poster child for “getting it wrong”, he makes me look like a sore winner.

@jbrains Yup! I try to emphasize to people that rules 2 and 3 build on each other and you need to iterate. Doesn’t matter which is first.

— Corey Haines (@coreyhaines) December 7, 2013

He goes on to say this.

@angelaharms @jbrains Honestly, I always have a hard time remembering which one is 2, which is 3, so I just sort of right them however.

— Corey Haines (@coreyhaines) December 7, 2013

He also has a hard time writing “write”, but we love him just the same.

References

J. B. Rainsberger, “Three Steps to a Useful Minimal Feature”. This article describes one of the key techniques of Product Sashimi.

Kent Beck, Extreme Programming Explained. Where I first learned these rules of simple design.

-

I use “simple” as shorthand for “lowers the cost of future features”. For more, watch “The Economics of Software Development” or, if you prefer to read, I plan to write more about this at jbrains.ca.↩︎

-

Thus, “your code is trying to tell you something”.↩︎

Comments